In American military hospitals, patients were separated into wards by type of illness. Psychiatric and TB patients had their own wards, and other troops were grouped by injury type or disease. Librarians inspecting military hospitals at home and abroad noted that each hospital had its own way of dealing with the fear of contagious books. “It was here, . . . that an ingenious plan had been conceived to care for the books in the contagious wards,” noted librarian Mary France Isom of her inspection of an American military hospital in Toul. “A neat little white bookcase had been provided for each ward and to prevent the books from straying, each was marked with an appropriate color. A sinister band of yellow pasted across the binding denoted smallpox, there was red for scarlet fever, green for meningitis, a dainty blue for the less objectionable measles, and so on.” This system was based on a simple principle. Once a book entered a contagious disease ward, it never left. Special bindings helped to prevent cross contamination between wards.

At home, military hospitals, like the one in New Haven, Connecticut, drew on local public libraries to help fill patient requests. However, some public libraries refused to lend books to hospital libraries that served patients with TB or other contagious diseases. “Many public libraries are unwilling to lend their books to patients in the tuberculosis hospitals, either government or private,” Modern Hospital reported, “and the American Library Association is trying to remedy this by sending books from its tuberculosis hospital library.”

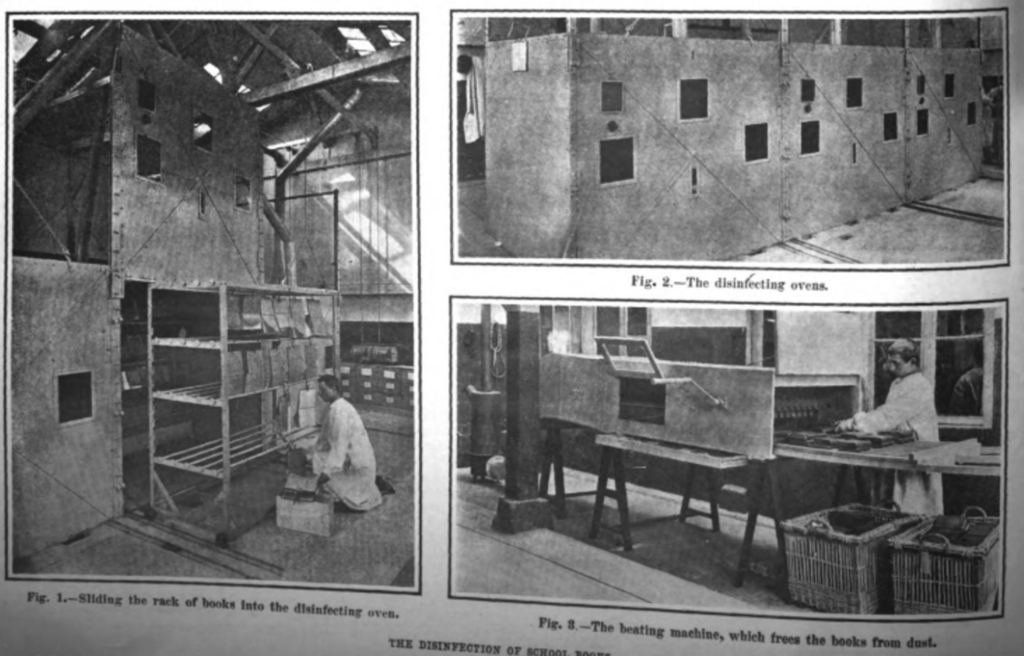

The belief in the power of books to spread disease endured throughout the war despite existing methods to disinfect books. Some librarians baked books in ovens to kill germs, and the most common method suggested by experts dictated a book be left in sunlight for 48 hours after contact with an infected reader before it could be put back into circulation at a public library.